How safe are your bonds now?

With interest rates on the floor

Many advisers will tell you that ‘bonds’ are the ‘safer’ part of your investment portfolio.

“Your bonds will protect your funds if the riskier part (your shares) crash in value” is what they say.

But that’s only right some of the time.

Read on to find out how safe bonds are now – with interest rates on the floor

if the security of your money is important to you, and you have some reasonably big sums in the bank . . .

. . . start with this other Insight on the ‘safety’ of bank deposits.

What sort of bond are we talking about?

And before we start, let’s be clear about what this Insight is about.

The bonds we’re going to talk about here are the ‘asset’ type.

You might also have heard about (or perhaps you hold) an investment product wrapper called an investment bond (aka insurance bond) but these are quite different things.

Insurance bonds are a type of ‘investment ‘box’ (or wrapper) issued by insurance companies.

And, just like a ‘pension plan’ – an ‘insurance bond’ is simply a box in which you hold your investment assets.

So, the sometimes confusing thing is that you can hold ‘bonds’ (and cash deposits and stocks and share funds and property funds) inside an insurance bond 😊

Now that’s enough about the Insurance bond wrapper (for now)

Let’s talk about the asset class of Bonds and start to understand the risks there.

What are bonds

You’ll often hear Bonds described as a ‘gentle step up’ (from bank deposits) on the investment risk scale.

And a typical ‘mixed’ (aka ‘multi asset’ or ‘balanced’ or ‘diversified’) type of fund (aka ‘portfolio’) will hold a fair chunk of bonds in the mix.

At a basic level, Bonds are simply loan contracts – issued by companies or governments when they want to borrow money.

Governments (and local authorities) borrow money for many reasons. To build roads, schools and hospitals for example.

Companies can also raise money for new buildings or other new business expansion projects.

The UK versions of government bonds are called ‘gilts’ and company bonds are called ‘corporate bonds’.

Most bonds (but see later) offer a fixed interest regular income payment (called the ‘coupon’) and then ‘mature’ at a set point in the future. That’s when it’s expected that the borrower will repay the original loan amount.

So, if you invest in a bond you’re ‘sort of’ lending money to the government or company that issued it.

I say, ‘sort of’ because in most cases you won’t need to hang around to the bond’s maturity date (when the loan is, hopefully, repaid) in order to access your money.

You can decide to sell your bond (in the markets) before it matures.

You just need to be aware that when you want to sell it – you may get back less (or more) than you paid for it.

And whilst there is usually a ready market for government bonds, corporate bonds can be difficult to sell if there are very few buyers and sellers for the bond you hold.

* Bonds with different features

Some (zero coupon) bonds make no regular payments. So, the total return you receive on these types of bond depends entirely upon the maturity value or the market value if sold earlier.

Other (undated) bonds have no end date, so your total return depends on the regular payments and the market value when the bond is sold on.

And some types of bond offer inflation-linked returns on both the interest payments and return of capital. These are sometimes called ‘indexers’.

If you buy a bond at launch (when it’s ‘issued’) and hold it to maturity, then you’ll get your capital back provided that the borrower doesn’t default.

However, if you buy bonds (in the open market) after they’ve been issued and/or you sell them before they mature, then your capital is at risk.

You might make a profit or suffer a loss, because prices will vary in the interim period.

Holding bonds inside a fund

Most private investors hold bonds inside open ended ‘Collective funds’ where their money is ‘pooled’ with that of other investors – and the fund is run by a professional fund manager according to a set of objectives.

The price of these bond funds – and hence the returns you can make from them – can rise and fall over time.

And the ‘variability’ of price in any bond fund will depend on the type of bonds it holds.

What makes some bonds ‘riskier’ than others?

Well, the riskiness of bonds (the amount by which prices could rise and fall between purchase and sale) depends upon various factors, including:

- market expectations for future inflation and interest rates

- the time left to the maturity of the bond (aka duration risk) and

- the financial standing of the borrower*

* When investors begin to question the solvency of a borrower, the value of their bonds can fall sharply in value – pushing their ‘prospective’ yields up.

When bond prices fall – the yield goes up (and vice versa)

Imagine a bond paying a fixed income of £5 each year for each £100 worth of bonds held.

In other words, the yield on this bond is 5% p.a.

If investors get nervous about one of those risks listed above they might start selling the bond. And if it’s price crashes by, say, 50% then that £5 p.a. fixed income now equates to a running yield (for the new owner) of 10% (£5 per £50 of the new value)

Now, the new bond holders might consider that they now have a great investment. If they expect the price to recover from £50 back to ‘par’ (so that the full £100 loan is repaid at maturity) then their prospective total return (aka ‘redemption’ yield) would be very high.

They’d enjoy the continuing fixed income payments and a doubling in the capital value of the bond to the maturity date.

So, their total annualised return would be a lot more than the new 10% p.a. running yield.

Of course, the original bond holders will have had a reason to sell out. They may not have thought that the bond issuer (the borrower) was ‘good’ for the money.

They might have thought that some or all of the future income and the maturity proceeds would not get paid out.

So, a bond which yields a lot more than others of the same type should give you a warning that it carries a higher risk.

The lesson is NOT to get lured into chasing high bond yields from highly indebted companies.

Your capital may be a lot less safe than in a low yielding UK or US government bond.

You might also want to keep Greek Government bonds off your list of super safe assets too.

Historically, UK Government bonds (gilts) have been viewed as very secure.

That said, the leading ‘ratings’ agencies have recently started to downgrade the UK’s credit rating. So, they are obviously getting concerned about our ability to service our debt in the future and they might have a point!

But with our own central bank – the UK government is likely to keep all it’s promises to repay it’s debts. The bigger risk to investors in longer term gilts comes when inflation expectations rise.

Holders of developed economy government Bonds, might normally get all their money back . . . it might just be worth a lot less, in real terms, than when they invested 🙁

The final key point to note here is that a corporate bond is often viewed to be less risky than an ordinary share issued by the same company. And this is because it’s the shareholders who get ‘wiped out’ first in the event of a company going bust.

If there are some assets left over in the company after priority debts are paid (such as those to the taxman) then the bond holders may receive some residual return.

However, in an extreme case of insolvency it is possible to suffer a total loss on bonds – just as it is with shares.

The long bull market in long bonds

Bond (or stock) markets in which prices have risen a great deal over a long period of time are called ‘bull’ markets.

Those in which prices are trending downwards are called ‘bear’ markets.

Bonds have been in a bull market for a very long time now.

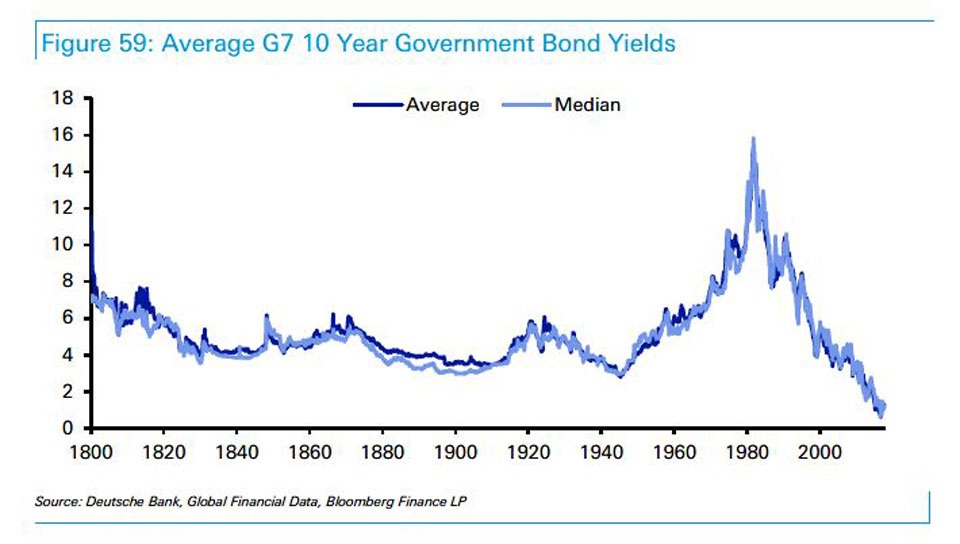

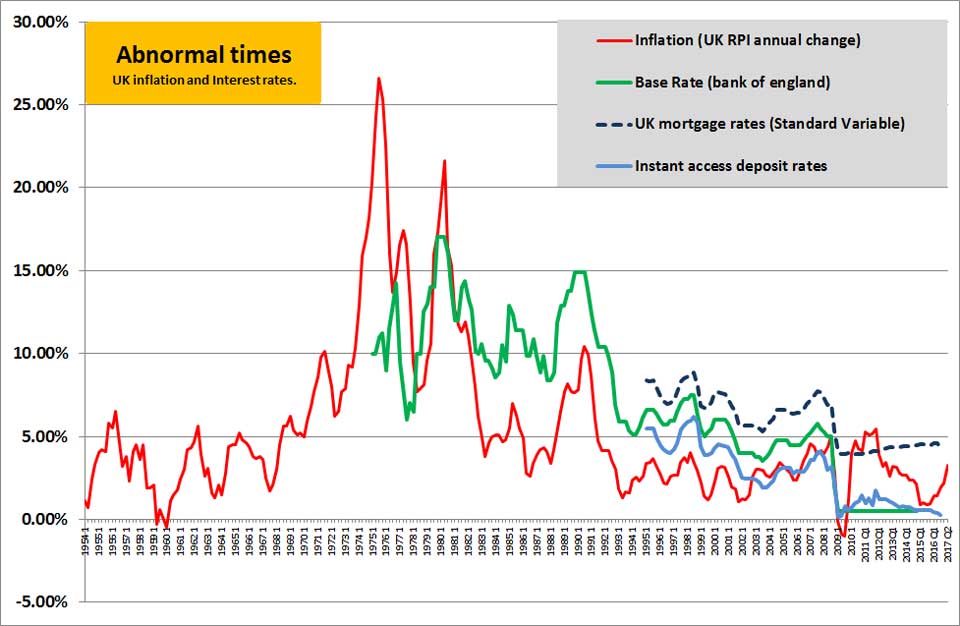

And this is largely because inflation and interest rates have been falling for a very long time too – as we can see here.

So, bond investors have (for 40 years) enjoyed some extremely good returns.

The yield on long bonds has been in almost continuous decline – alongside inflation. See below.

And, as we’ve seen above, for fixed income bond yields to fall – their price has to go up

And that’s why most bonds are much riskier now

And that’s why most bonds are much riskier now

Unfortunately (and as always happens) this long ‘bull market’ in bonds has led to ‘less informed’ advisers promoting the past performance of this asset class.

Advisers should not do this. Indeed, they’re breaking the regulations set by the financial conduct authority if they do so.

And, if there’s one thing that gets me super IRATE® about investment sales people it’s the constant use of past performance tables to sell.

So, please, whatever you do . . . take your time to read the warning that should be clearly marked on any investment product you buy.

It should read something like this:

Sadly, very few investors do read this script . . .

Sadly, very few investors do read this script . . .

. . . and next to nobody reads it towards the end of extended bull markets –when everyone’s caught up in the ‘euphoria’ of high returns.

The fact is that some advisers promote funds based on past performance. And that’s a particularly dangerous and misleading thing to do at this stage in the interest rate cycle.

The truth is that not all companies (or governments) always repay their debts!

So, if you’re going to invest in bonds – you need to have (or hire) some expertise about the credit risk of the various borrowers.

And you need to take account of the other risks mentioned above.

Some advisers (and online bloggers) will tell you that you can ignore these details.

And some will suggest that all you need to do is ‘track’ a bond index of what they might consider to be safer types of borrower – like the UK or US governments.

They might even show you some past performance data to prove how well you would have done – had you been lucky enough to have followed their simple rule in the past.

So, what could possibly go wrong?

Well let me walk you through a example.

How the price of the ‘safest’ bonds could fall hard from here.

I’m going to make this super simple for you – and for me 😊

So, I’ve run some numbers assuming that you’ve invested in a long term (30 year) ‘zero coupon’ UK government bond for this example.

The ‘outcomes’ that I’ll show you would be less ‘extreme’ for shorter term and higher yield gov’t bonds but this example will help you understand the point.

Now, imagine that you’re living in more ‘normal’ times – when interest rates are not at their current ‘crazy’ lows.

And imagine that you’ve invested into a relatively low risk (UK or US government backed) 30-year zero coupon bond with an expected nominal return (to maturity) of around 5% p.a.

Then, let’s roll the clock forward 5 years, during which time inflation falls constantly along with (short and long) interest rates. And that your (now, 25-year) bond yield has fallen to just 2% p.a.

What do you think this will have done to the price of your bond?

Any ideas?

Well, I can tell you.

It will have pushed the price up by about 160%.

Yes, that’s right.

That ‘boring’ old bond will have more than doubled in price.

And that’s the sort of thing that’s been happening on long bonds for 40 years now.

As we’ve seen above, as inflation and interest rates came crashing down. Bond prices went up . . . and up . . . and up some more.

Typical developed market (10 year) bond yields have dropped from around 15% p.a. to around 1% p.a. over this time.

And as we’ve already seen from this chart – this is simply not normal territory.

So, now let’s think about what could happen if this situation is reversed.

What if we start from a point where long-term interest rates are super low (like now) and rise a bit over the next 5 years.

Let’s say that your starting 30-year bond yield is 2% p.a.

And then 5 years later the 25-year yield has ticked back up to 5%.

A very possible scenario – wouldn’t you think?

And especially so if a ‘borrow and spend’ government (the sort that Jeremy Corbyn is planning) is in power by then 😉

Super low borrowing costs for our government might seem like a distant dream if that happens !

Anyway, regardless of who’s in government . . .

what do you think that a gentle move up in long term interest rates would do to the price of your 30 year bond?

Well, it would drive the price down by around 50%.

That’s right.

Your nice safe bond would halve in value.

Ouch!

Of course, long term interest rates could conceivably stay where they are for a while or even carry on falling further to the floor. And if that happens then long term bond prices could be supported a while longer.

But I don’t know of any intelligent commentator who’s predicting that. And most agree that we’re now at or near the end of this long bull market in bonds.

Even Alan Greenspan (the former head of the US central bank) has recently said that we’re facing a big ‘bubble’ in bonds right now.

For more on his views watch this

Either way, if you want your bonds to protect your portfolio in the event of a downturn in your ‘risky’ assets . . .

. . . you might want to avoid having too much exposure to the riskier types of bonds (those with a long duration and / or lower credit ratings)

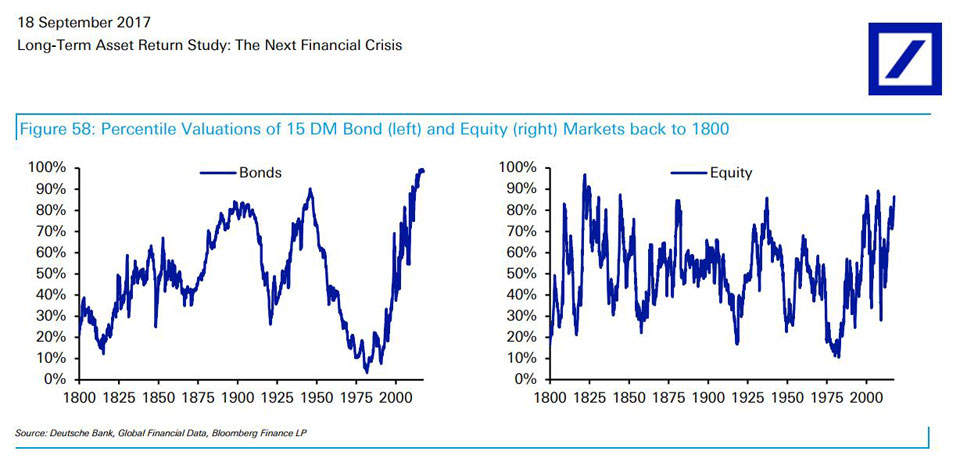

A recent report by Deutsche bank suggests that ‘Bonds’ have never been more expensive than they are now.

Here’s their evidence.

And note from the right hand chart that – as I’ve shown elsewhere – it appears that shares (aka stocks or equities) are also ruddy expensive right now too.

So, the old idea that bonds and equities are ‘uncorrelated’ assets (when one falls the other goes up) only works some of the time.

In a real crisis there’s only one thing that goes up – and that’s correlation 😉

Sometimes, both asset classes do fall hard – in concert – like they did in the 1970s

Conclusion

The next time any adviser (or online blogger) tries to tell you about the wonderful past performance of bonds (or any other asset class) . . .

. . . just tell them to get real and study some history . . .

. . . and to read that risk warning above

Bonds can be tricky beasts.

They’re not all, nice, simple safe assets.

And trying to make things simple by tracking a medium-term bond index is a risky strategy right now.

So make sure that your adviser understands these facts and that your bond funds (if you have any) are well managed by bond experts too.

And have a great day 😉

Paul

Please share your thoughts in the comments below.

I’d love to hear from you.

You can log in with your social media or DISQUS account OR To “post as a guest” – just add your name and that option will pop up.

And for more ideas and updates – straight to your inbox – click this image

I’ll also send you a chapter of my acclaimed book AND my ‘5 Steps for planning your Financial Freedom’ (absolutely FREE)

I’ll also send you a chapter of my acclaimed book AND my ‘5 Steps for planning your Financial Freedom’ (absolutely FREE)

Discuss this article